First, there was the German Giant. Then there was the Swedish Lion. And now it’s time for the Norwegian language to get the Transkribus treatment with the new NorHand model.

This AI text recognition model, developed by the National Library of Norway, has been trained on over 400 different hands, including the writing of famous authors such as Sigrid Unset. The library has also decided to make the NorHand model public, meaning that everyone can benefit from the high-quality text recognition it provides.

We spoke to Yngvil Beyer, head of the Language Bank and Digital Humanities Lab at the National Library, to find out more about the creation of the NorHand model.

The challenge of digitising handwritten documents

Making cultural heritage accessible is a key goal for libraries, and the National Library of Norway (NLN) is no exception. “Digitisation is a crucial way to make cultural heritage widely accessible,” Yngvil explained. For that reason, back in 2005 the library set the goal of digitising all their materials and making them available online. They began this process by digitising printed books using conventional OCR systems, before starting on the library’s collection of newspapers. “We have now digitized almost all the books and over half of the newspapers in our collection.”

But the library’s handwritten manuscripts presented more of a problem. The OCR systems that had worked successfully for printed materials did not return good results with the handwritten documents. After trying out a few different systems, Yngvil’s team decided to go with Transkribus. “Transkribus was easy for us to adopt. It has an accessible interface, and we can use both our own and their API to ensure good data flow.”

Training the NorHand model

Transkribus’ ability to let users train their own AI models was also a key benefit for the library. “For us, it [was] crucial that one can train models without needing machine learning expertise”. This was particularly important as the majority of the training and preparation of training data would be done by library staff and students, who don’t necessarily have a technical background.

Yngvil’s team made the sensible decision to start small. “When we started using Transkribus, we trained several author-specific models. These worked well for processing material for authors we had a lot of material from, such as well-known authors like Sigrid Undset.”

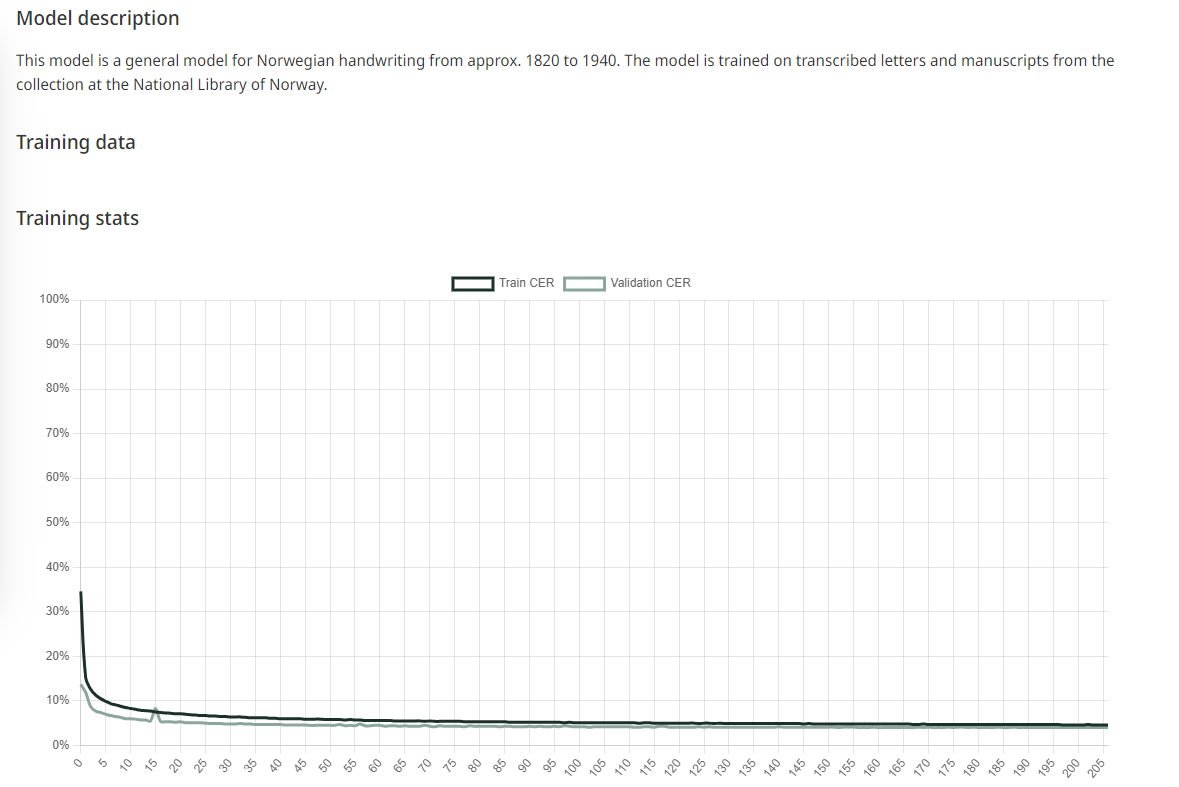

After successfully training many of these author-specific models, the team then compiled all of the training data and created one large model, capable of deciphering Norwegian handwriting from the 19th and 20th centuries. “[The model] is now trained on around 400 different authors, and we see that it generalises well, meaning it can effectively recognize text from authors it has not been trained on.”

Tough transcription decisions

While the team found the training process to be fairly easy, there were several not-so-easy transcription decisions that had to be made as part of the process. “We quickly realized that we had to make several choices. Some of these choices have been adjusted along the way, such as how we handle corrections, inserted words, and lines that do not follow the reading order.”

For example, in Transkribus, many people use the strikethrough markup to indicate a deleted word in the text. However, the NLN’s online library does not support the strikethrough markup. Instead, the library presents words that had been marked with a strikethrough in Transkribus simply as part of the text, as shown below:

“We therefore had to choose between annotating deleted words in Transkribus, or just skip them, or adjust the layout so deleted words are omitted. There is not always a match between the best way [...] to create the best possible model and the best way to make the text available to users.”

Putting the model to work

The library’s goal was to have a model that they could use to transcribe the vast volumes of handwritten documents in their possession. This goal has definitely been achieved — approximately 25% of the library’s scanned documents have already been processed with Transkribus and published online in the NLN’s digital library. What’s more, the digitised documents are fully searchable, making it possible to quickly find all the documents relating to a certain keyword or phrase.

The team also took the community-minded decision to make the model available for everyone to use. “We share both the model and the training data openly, and we know that many other institutions in Norway are now using our model.” You can try out the NorHand model for yourself on the Transkribus platform.

An ever-moving beast

The first version of the NorHand model was published in September 2023. But the work didn’t stop there. “We wanted to make the model more general, so when we had new transcriptions, we added them and trained a new version of our model.”

By continually updating the NorHand model in this way, the library can ensure that the model is constantly improving, and is able to recognise an increasingly diverse range of hands. Because of this, it is an effective model for any handwritten Norwegian text from the 19th and 20th centuries.

Yngvil’s advice for others

The NorHand model has been a successful project, and the team has learnt a lot during the process. We asked Yngvil what tips she would have for other libraries and institutions embarking on a similar project.

“Build competence and interest within the institution. And start with material that someone is interested in, so that they can, for instance, help proofread the annotations.”

Thank you, Yngvil, for sharing your experience with us!